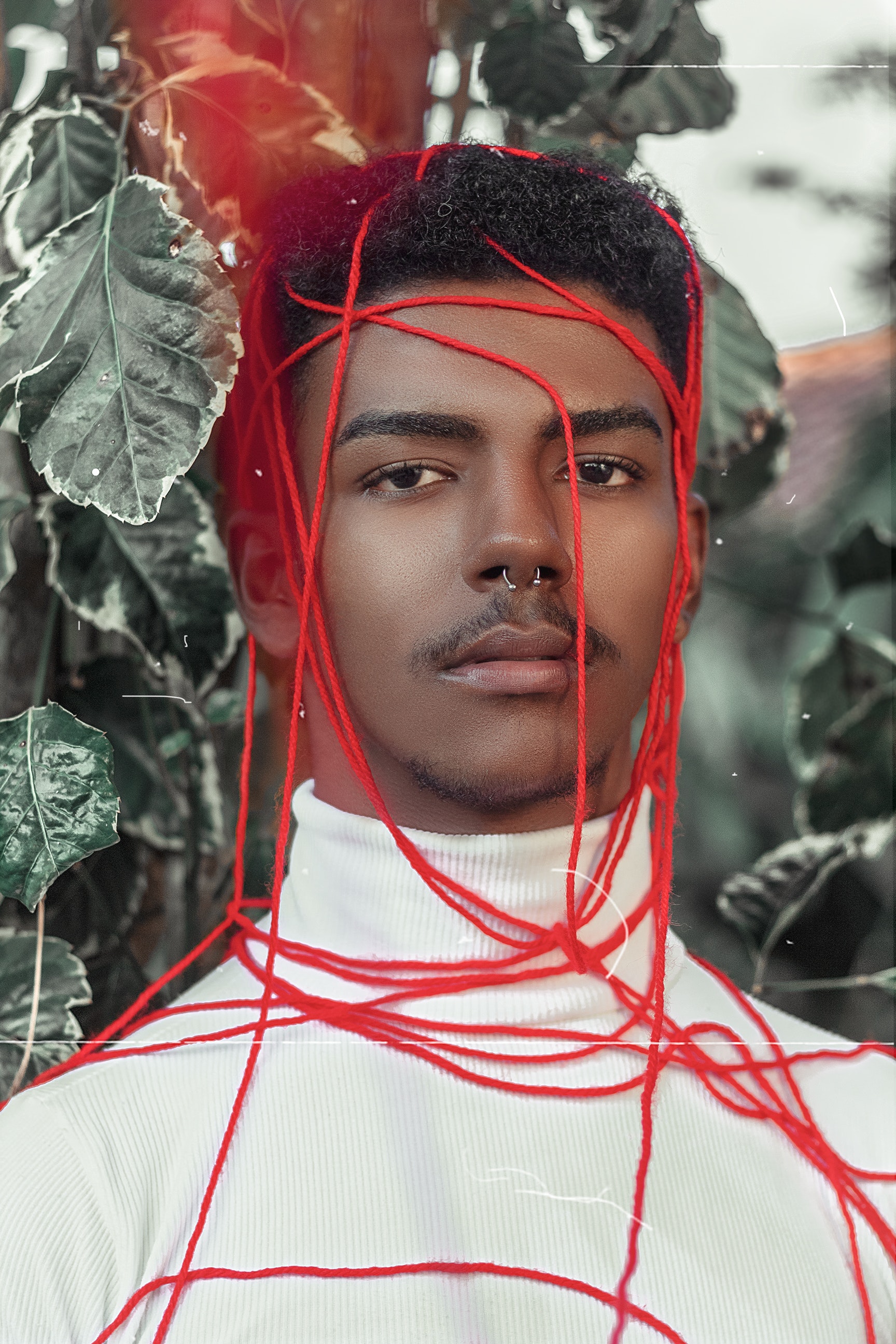

&stress about &Strings

There’s one — a few — lots — even dozens — of good articles that explain the differences between a &str, &'static str, &'a str, String, and &String in Rust.

Most of these start by covering:

- the heap and the stack;

- ownership, and;

- lifetimes;

and while that’s all important, it can feel like a lot when you’re starting out.

Let’s try something different.

Here, we’ll use an analogy, and look at some code along the way.

Analogies ain’t perfect, but I hope this one makes the topic stick better for some of you. If it does, you can return to those other articles with some intuition.

You run a desk nameplate business for dogs

Bear with me here.

You want to set up a business where you sell plastic desk nameplates for dogs in high places.

To make these nameplates you have two options:

-

Get some real nice steel moulds made up, and bolted to a shelf in your shop (you can only do this once, ever). You can point to a mould, and your technician will carry a bucket of molten plastic over to cast a nameplate.

-

Send the dog’s name to a 3D printing company and ask them to make you a nameplate on demand.

&’static str: point a finger at moulds you’ve committed to

Check you out. You’re smart. You’ve done some market research about dogs, so you know ahead of time that you’ll get lots of requests for “Max”, “Charlie”, and “Rolo” nameplates. For these names, it would make sense to get a stack of steel moulds made up ahead of time.

Let’s do this for “Rolo”:

fn main() {

let point_finger: &'static str = "Rolo";

hot_plastic(point_finger);

}

// Ask your technician to pour plastic in, get nameplate out

fn hot_plastic(steel_mould_location: &'static str) {

println!("{steel_mould_location}");

}The name "Rolo" in the code above is a “string literal”: a hard-coded string defined in the binary of your program. String literals are objects with a static lifetime — this means that they will last for as long as our program (or business) is running. You can think of string literals as being like steel moulds, or the laws of the Universe — they are unchanging and unchangeable things that will always be there in memory.

point_finger, on the other hand, is not a string literal: it is a variable that makes reference to the string literal "Rolo". It has the type &'static str:

- the

&part means that we’re pointing to a reference, a “place” — that place is the fixed location on the shelf where your steel mould is bolted; - the

'staticpart means that we can safely point at this object forever (after all, we’re pointing at a steel mould, so it will always be there).

Imagine you lose your finger in a freak accident. If you plan ahead, then you can still use other methods to point to the right location on the shelf:

fn main() {

// Let's go out and buy a signpost

let use_signpost: &'static str;

{

// Use your finger to point at a steel mould

let point_finger: &'static str = "Rolo";

// Write on signpost so that it also points there

use_signpost = point_finger;

} // Oh no. You lose your finger here.

// If you try this:

// println!("{point_finger}");

// it won't work, cause you ain't got no finger now.

// But this is fine:

println!("{use_signpost}");

}So you see, the variable point_finger isn’t static, it just directs us to something which is. Fingers can be created or destroyed.

Getting this “Rolo” mould made up as a string literal required foresight, didn’t it? At compile time, you had to know that you wanted to commit resources (be that money or memory) to the name “Rolo”.

In return, you get certainty. The steel mould will always be on the shelf, and nobody (not even you) can ever move it, hide it, or change it (we say that 'static str are “immutable”).

These constraints could be annoying in some circumstances, but you’re happy because you know you’re going to use this mould a lot.

While string literals are not mutable, &'static str variables are mutable. You can use your finger to point at other things:

// point at the "Rolo" mould

let mut point_finger: &'static str = "Rolo";

// now point at the "Max" mould

point_finger = "Max";Something that might cause confusion: if you type let steel_mould = "Rolo", your IDE will probably display let steel_mould: &str = "Rolo". It says the type is just a &str without the 'static part. Even though your IDE doesn’t explicitly say it, this &str is a &'static str.

String: committing resources to unspecific tasks

Would it make sense to make steel moulds for every dog name that exists? Not if you want your business to stay afloat! Some names will be rarer; they aren’t worth such a specific investment.

If someone comes in and asks for a nameplate for their completely normal dog called “Harambe794524”, then we’re better off sending that to the 3D printers.

There are three steps to sending a dog name to the 3D printers:

- we ask the customer what their dog’s name is, and write it down on a note;

- we send that note to the 3D printers, and then;

- they produce a nameplate that they send to the customer.

They don’t return our note to us — we don’t need it.

fn main() {

// Get your peice of paper ready

let mut original = String::new();

// Ask for the name of the dog and write it down

std::io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut original)

.expect("Failed to read input dog name");

// Send the note to the printers

threedee_print(original);

}

// The printers will print the nameplate

fn threedee_print(note: String) {

println!("{note}");

}In this analogy, our written note is a String. A written note or a String is a good choice when:

- we can’t anticipate what a dog’s name will be when we open our business (we have no foresight at compile time), and/or;

- we want the option to alter what we’ve written down — a notes or a

Stringcan be mutable (unlike a steel mould or string literal).

We still want to fulfil these orders for weird dog names because we’re a business and we flippin’ love money. This means we need to commit some flexible resources to this task, but we don’t know how many yet.

The requests for dog names might be short names, they might be long, we might get hundreds of names, thousands, or even none.

To be safe, we keep a heap of paper and pencils aside just in case (paper and pencils are computer memory here, by the way, yeah-I-know-you-knew-that).

Could we send the location of a mould to a 3D printing company who are expecting written notes? In other languages, you could totally do this and expect the language to handle the conversions, but in Rust, the answer is rigidly “no”.

You’ve lost your note!

Disaster strikes. The 3D printing company started printing one of your doggy nameplates, but the print failed and they already threw your note away. The customer is waiting.

It was “Harambe” something, right? But can you remember the sequence of numbers? Chances are that you’ve forgotten, and what’s worse, you sent (or “moved”) your one copy of the note to the 3D printers, and they don’t give it back!

You can try calling threedee_print(note); again in your program, but the Rust compiler will rightly tell you that you’re trying to do the impossible and re-use a note that you no longer own.

This is the problem with sending a String to a function. As soon as you send your one copy, you’ve lost it. You can’t use it again for anything else.

So, what are your options? Well, next time, you could:

- make a clone of your note and send that instead;

- ask the 3D printers to start returning a copy, or;

- keep the note, put it up in your shop window, and tell the 3D printers that they need to send someone round to look at it.

All of these approaches can be used in Rust.

1. Make a clone()

Cloning the note before we send it means we can use the original note again afterwards.

fn main() {

// Get your peice of paper ready

let mut original = String::new();

// --snip-- (ask customer for dog's name, write it down)

// Make a copy of the note

let note_copy = original.clone();

// Send the copy to the printers, keeping the original

threedee_print(note_copy);

}In this case note_copy has “moved” into the function threedee_print, and therefore it is no longer in scope of main.

We haven’t moved our original, so it stays in scope, and so we can use it again.

2. Returning the String

Asking the 3D printers to return a copy of the note, or the original note, is achieved by modifying the threedee_print function.

// The printers will print the nameplate and return the note

fn threedee_print(note: String) -> String {

println!("{note}");

note // give a copy (or the original) note back!

}We actually have no way of knowing whether the 3D printers have returned the original note, or an identical copy of it. They’ll do whatever is most efficient, and the Rust compiler is exactly the same in this regard.

Worrying about whether we have an original or a copy is academic — we don’t care — we get an accurate note back, and so can now call:

let note_back = threedee_print(note);

in our main function, and continue to use note_back as we please.

3. Use a reference with &String

Our last option was to put the note up in our shop window, and ask the 3D printers to look at that note and use it as a reference:

fn main() {

//-- snip --

// Tell the printers to look at your copy

threedee_print(&original);

// Do it again if you like

threedee_print(&original);

}

// The printers will print the nameplate based on a reference

fn threedee_print(shop_window: &String) {

println!("{shop_window}");

}The ampersand in front of &original means were’re sending threedee_print a ‘reference to a String’, called a &String.

Using println! in this example isn’t great — println! does a lot of hard work in the backround to be useful, so it will print out the note regardless of whether we pass it an actual note, or point to where the note is (our shop window).

To illustrate what’s happening better, we’ll create a struct called DeskPlate. This struct is not clever like println!; it’s very strict about having dog_name as a String, and it won’t accept anything else.

Warning: This won’t compile.

// Define a struct for the Deskplate

struct DeskPlate{

dog_name: String,

}

// The printers will print the nameplate based on a reference

fn threedee_print(shop_window: &String) -> DeskPlate{

DeskPlate{dog_name: shop_window} // ! This won't work

}In the example above, we’ve told the 3D printers to try and create a DeskPlate based on a location (your shop window). Your shop window is not a dog’s name — it is a place where you can find a dog’s name, and so the code won’t compile.

We need to be more explicit. We need to tell the printers to make their own copy of our shop window note by using note.to_owned() or note.clone():

fn threedee_print(shop_window: &String) -> DeskPlate{

// Ask the 3D printers to make a copy of what they see in your shop window

let note_copy = shop_window.to_owned();

DeskPlate{name: note_copy} // This runs fine

}Doing this will make the code compile fine.

Converting between notes and moulds, String and &str

&’static str to String: easy peasy

Could we choose to 3D print a nameplate like “Rolo” even though we already have a steel mould? Yes, because we can always look at our mould and write down what we see in a note, converting a &'static str into a String like so:

fn main() {

let mould_location: &str = "Rolo";

// Let's write down a note based on what we see in our mould

let note = mould_location.to_string();

threedee_print(note);

}String to &’static str: hardy … pardy?

Converting a String to a &'static str is not so trivial.

The factory that makes steel moulds (i.e. the compiler) can do this, but it only gets run once.

After we’re running though? No chance. The best you can do is to hope that you already have a steel mould that matches your note, like this:

fn main() {

// Someone has given you a note that says Rolo on it

let note: String = "Rolo".to_string();

let mould_location: &'static str = match note {

_ if note == "Rolo" => "Rolo",

_ => panic!("I don't have the mould!")

};

}What you’ve done here, is looked at the note, gone into the back room and tried to find a mould that matches your note. If the note says “Rolo”, you’re in luck, because past you was wise. Nice.

Did you get given a name that you didn’t anticipate when you set up your business? Well you ain’t using a steel mould then, matey*.

*Kind of. There are ways to leak the memory of a String to produce a &’static str, but they go beyond the scope of this analogy, and it’s probably not something you’ll do a lot.

String to &’a str: you can do this

A customer with a dog named “Lord Gumzies” is insisting on a moulded nameplate, they do not want a 3D print because “3D prints look all weird and ribbed”.

While you can’t make a new steel mould, you could try and cobble together your own mould out of polystyrene, and leave it lying on the shelf. Your polystyrene mould won’t last as long as a steel one, and it might move.

A polystyrene mould is what a &'a str is. That cheeky 'a thing is similar to 'static from before, and it’s called a “lifetime”. &'a str has a lifetime specifier 'a which tells you how long we can safely point to the polystyrene mould (after that lifetime is up, we’re no longer guaranteed to find it at that location).

Rust’s compiler can often (but not always) figure out how long a variable or reference needs to last for, all on its own. Well done, Rust.

To convert a String to a &'a str, we do this:

fn main() {

// Get your peice of paper ready

let mut original = String::new();

// Ask for the name of the dog and write it down

// -- snip --

// Make a polystyrene mould

let poly_mould = original.as_str();

}Beware reader, be very ware. The use of the term “str” in the as_str() method doesn’t mean you’re producing a string literal or a &'static str. In fact as_str() will produce a mould with a lifetime which is not static.

A &'static str needs to be a valid reference for as long as our program runs, so the objects it points to must be permanent. If we define an object after compile time, that means that we don’t have a permanent object by definition.

This all matters because if we try to pour hot plastic into our polystyrene mould:

Warning: This won’t compile.

//Pour plastic in, get nameplate out?

hot_plastic(poly_mould); // ! won't runwe’re going to end up with a hot mess. Remember, the function hot_plastic is expecting a &'static str — our technician is expecting to be pointed to a permanent steel mould.

Instead, we’ve pointed out a polystyrene mould that “might still be there”, to a technician who is carrying a bucket of piping hot liquid death.

How can we solve this? We need to define a new function, a new role for our technician, one which accepts a &'a str. Here’s one:

// Pour silicone in, get nameplate out

fn silicone(any_mould: &str) {

println!("{any_mould}");

}We can now pass this function a poly_mould: &'a str and it will work.

Hawk-eyed eagles among you have noticed that the function silicone can be passed a &str, but I told you earlier that a &str in your IDE always means &'static str, didn’t I? Yeah, when you’re defining string literals. If you see the term &str in a function’s arguments, it implicity means &'a str. This switching up of nomenclature will feel natural and totally cool one day, I promise.

Using a &’static str in a &’a str function

We can pass the fn silicone a &'a str, but can we pass it a &'static str? Can we ask our technician to pour silicone into a steel mould?

Yes, because the function silicone is not very restrictive: our technician doesn’t need to be pointed to references that will be valid “forever”. In this role, our technician will accept references that last any amount of time, including forever.

Summary

If you understood how to run a desk nameplate business for dogs, then you understand the logic behind Rust’s approach to string types.

Now go back and try again. Read all of those good articles that talk about the heap, the stack, ownership and lifetimes. Keep this analogy of writtten notes and steel moulds going if it helps you, but drop it once it becomes cumbersome.

Woof.